-

-

Written By Sento Kai Kargbo

Edited by Shane McAuliffe

Acknowledgements: A sincere thank you to the panel and presenters for their time and insights, and to the UK Research and Innovation (UKRI) for their support in the production of this webinar session.

Webinar Presenters

Helena Trigueiro, Dr. Minha Rajput-Ray, Alan Flanagan and Prof Sumantra Ray

Journal Club Presenters and Panel

Shane McAuliffe, Alan Flanagan, Prof Sumantra Ray, Helena Trigueiro and Dr. Minha Rajput-Ray

Webinar Summary

In June of this year, IANE and NNEdPro members gathered yet again for another session of our webinar series, on “Workplace Wellbeing – Diet, Mind, Movement, Sleep”, which, as the name implies, focused on health and wellbeing initiatives at work, especially with regard to dietary patterns of workers, movement and/or physical activity, and sleep. This blog aims to summarise key themes from the session, including main take-home points.

Recordings of past webinar and journal clubs can be found on the IANE portal.

As guests in attendance, we were welcomed to yet another webinar session by Shane McAuliffe, Science Communications Lead at NNEdPro, followed by an introduction of the evening’s line-up of presenters.

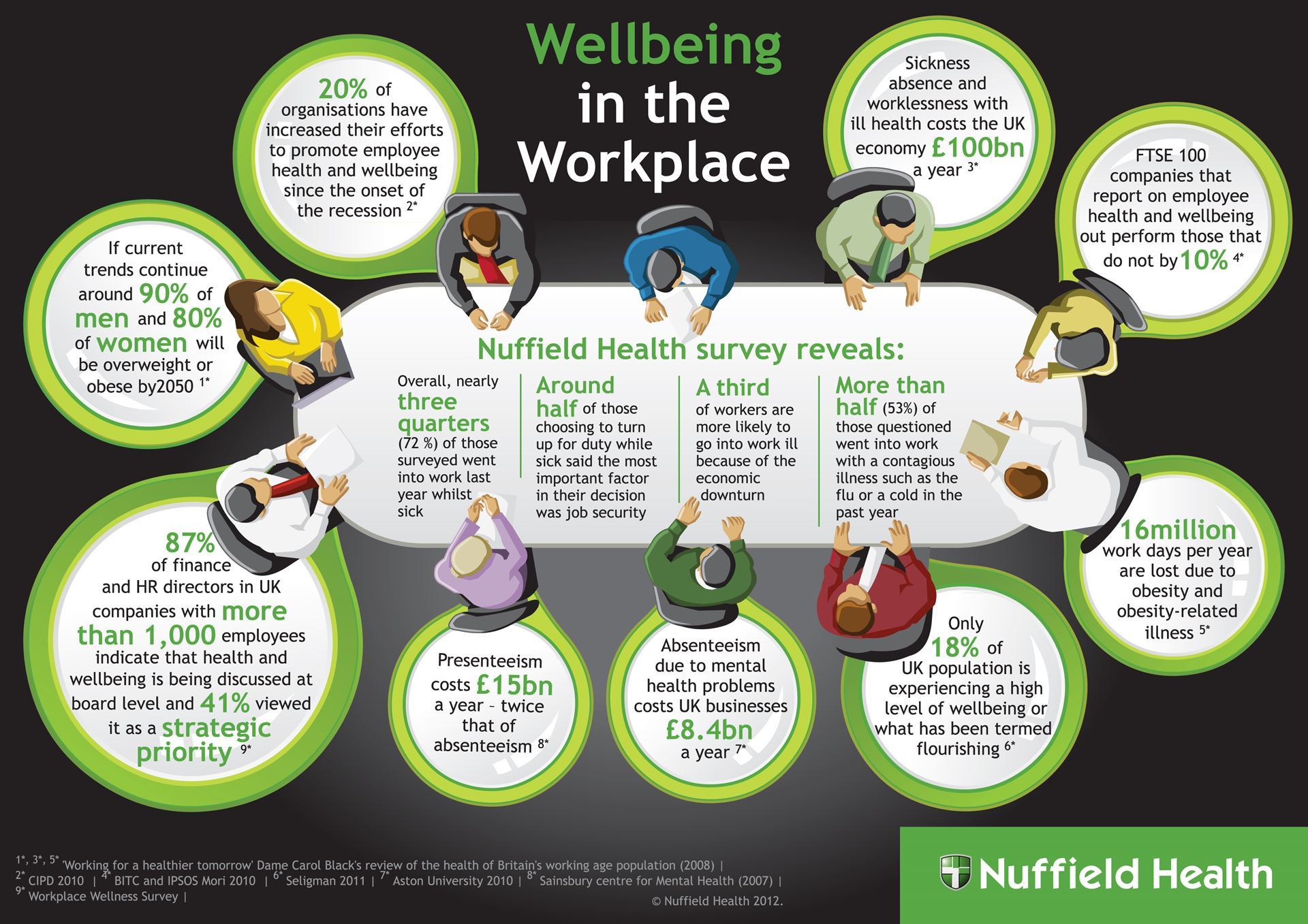

We first heard from Prof Sumantra Ray, NNEdPro Executive Director and Founding Chair, on the importance of wellbeing initiatives at work and the role of employers in health promotion. As part of his presentation, Prof Ray discussed the findings from the ‘Wellbeing at Work” survey conducted pre-COVID by Nuffield Health. Researchers found that one-third of workers were more likely to go to work ill, primarily due to job security and the economic downturn. Further, only 18% of the UK population reported experiencing a high level of wellbeing (“flourishing”) – an already dire situation that has been further exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic. As such, the workplace remains an optimal setting for health promotion, where employers are well placed to make significant differences in health behaviour such as regular health checks, taking breaks, nutritional advice, and increased physical activity.

Image 1. Infographic summarising key findings from the Nuffield Health “Wellbeing at Work” Survey.

-

-

On Food, Hydration, and Nutritional Supplements

-

✔ Poor diet quality can comprise immune function. A study by Kim H. et al (2021), recently published in BMJ NPH, found that plant-based diets and pescatarian diets are linked with less severe COVID-19 illness. This study included frontline workers from 6 high-income countries (Germany, France, USA, Italy, Spain, and UK). Plant-based diets or pescatarian diets had 73% and 59% lower odds of severe COVID-19 infection.

-

✔ Micronutrients (vitamins and minerals) are required in small quantities but are critical for metabolism and supporting optimal immune function.

-

✔ Our total body mass is >70% of water, and therefore, proper hydration is essential for improved health and wellbeing. Recommended minimum water intake (2-2.5L).

-

✔ A variety of physical, mental, and social factors overlap and interact to provide an overall effect on health and wellbeing which in turn impacts productivity. A productive society requires healthy workers!

-

In the second presentation of the evening, Helena Trigueiro (Global Lead for Regional Networks at NNEdPro) discussed findings from a web-based survey on global nutrition challenges during the COVID-19 pandemic. Survey participants were clinicians and researchers (n=30) across 5 continents – Africa, Africa, Asia, Oceania, and Europe.

Key findings include:

-

✔ Commonly cited government actions were support for hand sanitation (53.3%), assistance to school-aged children (46.7%) and direct food provision (43.3%).

-

✔ 50% of respondents perceived community actions and mutual aid as important aspects in the fight against the COVID-19 pandemic.

-

✔ Only 16.7% of respondents mentioned remote delivery of nutrition services in primary care.

-

Diet and physical activity, whilst crucial for improved health, are only a part of the story. Mindfulness and sleep patterns are also important in maintaining a healthy lifestyle, especially in the context of COVID-19. Our sleep patterns have been shown to influence our eating patterns as well as mental health. The role of community and social connections in wellbeing was also brought up. Commensality is an important factor in understanding dietary patterns and practice, and therefore, must be taken into consideration when designing interventions that target health behaviour.

In closing, Dr. Minha Rajput-Ray (Medical Director at NNEdPro and Scientific Chair for OSHA) shared her reflections on occupational health and wellbeing in the context of COVID-19, especially post-pandemic recovery.

Key Take-Home Points

-

✔ We must use the best available evidence to inform diet/’healthy-eating’ practices and advice that is suited to the context (context-specific).

-

✔ Be mindful of your food intake. Abundant consumption of plant foods (fruits, vegetables, unrefined cereals, fresh and dried legumes, nuts and seeds) is essential for health.

-

✔ Consistent sleep routines are also an important aspect of mindfulness, health and wellbeing, especially in the context of COVID-19. Sleep patterns have been shown to interact with dietary patterns.

-

✔ Physical activity and/or movement should be done in the way that makes you feel better.

-

✔ Community and social connections are also crucial aspects of mindfulness and healthy living.

-

✔ Workplace is one of the best settings for health promotion, therefore employers are well placed to make significant differences in health behaviour change such as regular health checks, taking breaks, nutritional advice, and increased physical activity.

-

-

Journal Club Summary

-

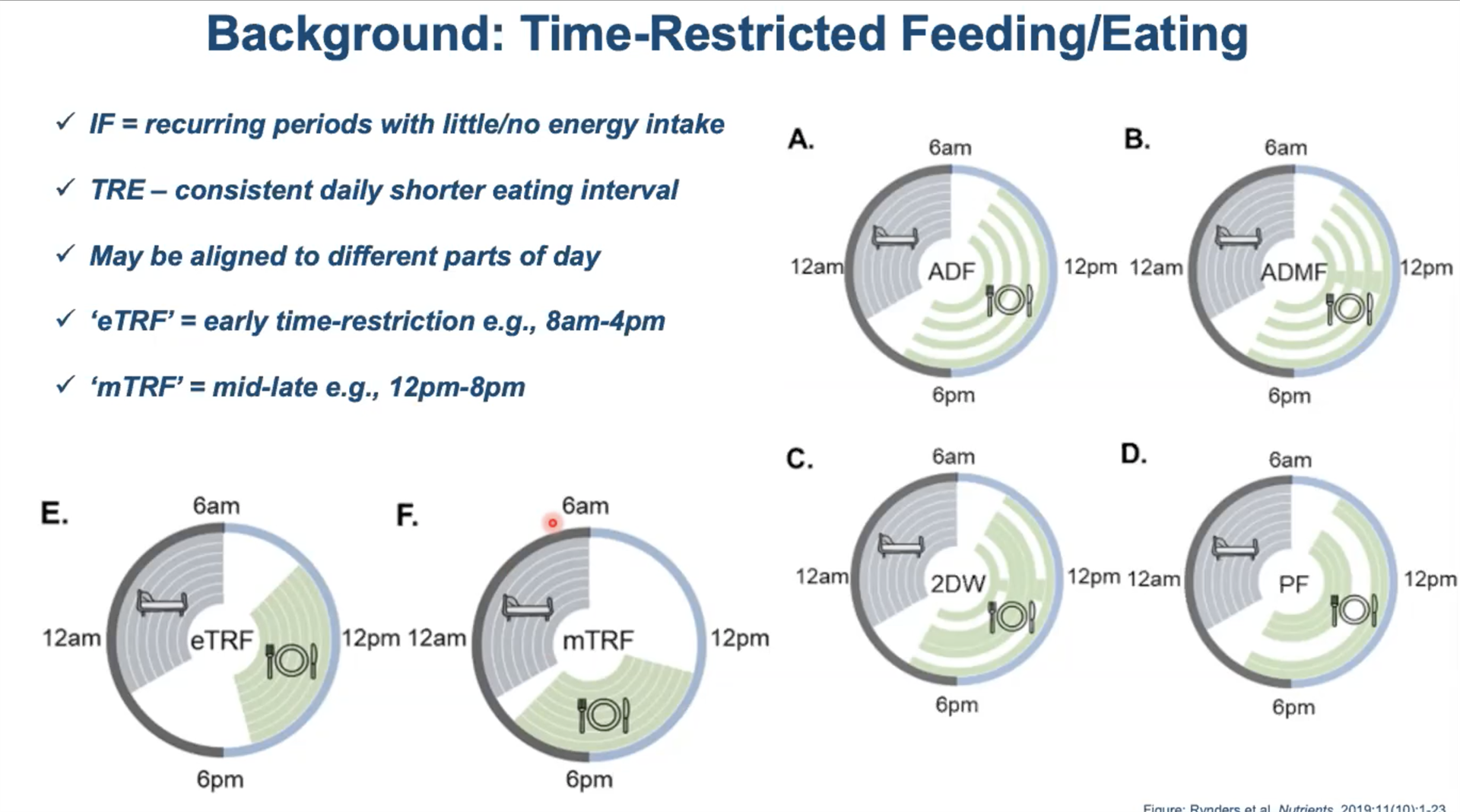

Following introductions and brief summary of the circadian (‘sleep/wake’) rhythm by Shane McAuliffe, our presenter for the evening, Alan Flanagan introduced the topic of – “Chrono-nutrition” which is defined as the interaction between biological rhythms and nutrition, along with the relationship between these factors and human health. Mr. Flanagan proceeded to distinguish between intermittent fasting (IF) and time restricted feeding (TRF) and led a critical analysis session on a recently published paper on a human trial of TRF.

Image 2. Difference between intermittent fasting (IF) and time-restricted feeding (TRF), including the types of TRF.

-

The Paper (Lowe et al., 2020): 12-Week free-living intervention comparing conventional eating window or ‘continuous meal timing’ (CMT) and time restricted eating (TRE) among men and women aged 16-84 years. The intervention was delivered through a mobile app and study participants were provided with a scale to weekly weigh-ins. Participants also received daily prompting via SMS messages. The primary outcome measured was weight loss.

-

Summary of findings:

-

✔ Overall, the TRE group experienced a weight loss of 0.94 kg (95%CI: -1.68kg to -0.20kg) higher than CMT group at 0.68kg (95%CI: -1.41kg to -0.05kg).

-

✔ Level of adherence was higher among the CMT group.

-

Strengths and Limitations:

-

This study included a larger sample size than previous TRE studies. Study included metabolic testing in 50% of total sample and robust measures of body composition. However, there was a lack vital data. Dietary intake and actual timing of meals timing was not performed. Differences in daily prompting (“gain-framed” vs “loss-framed” messaging) were not accounted for and compliance data was not presented.

Key take home points

-

✔ Chrono-nutrition focuses on behaviour as opposed to prescriptive dieting with the potential for improved metabolic health outcomes.

-

✔ Earlier research in chrono-nutrition were in animal studies, which tends to be problematic. Human diets and eating patterns are more complex and therefore we should proceed with caution when interpreting findings and/or referring to human populations.

-

✔ It is difficult to draw concrete conclusions from this study given the absence of important data points such as meal timing in the CMT group, the composition of the participants diets and issues with adherence.

-

✔ Further research is needed to account for these factors, as well as considering the effects of health messaging on behaviours and the applicability to specific groups, such as those with diabetes or cardiovascular disease and specific occupational factors (work patterns, break schedules etc.).

.png)